The following is an excerpt from the book Biplane written by Richard Bach, who is who is one of the foremost writers of aviation literature. What follows is the best explanation I’ve been able to find as to trying to describe the feelings one senses during a first flight. I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I do.

Morning, sun once again, and a fresh green wind stirring across the wing that shelters me. A cool wind, and so fresh out of the forest that it is pure oxygen blowing. But warm in the sleeping bag and time for another moment of sleep. And I sleep to dream of the first morning that I ever flew in an airplane…

Morning, sun, and a fresh green wind. Softly softly it moves, hushing gently, curving smoothly, easily, about the light-metal body of a little airplane that waits still and quiet on the emerald grass.

I will learn, in time, of relative wind, of the boundary layer and of the thermal thicket at Mach Three. But now I do not know, and the wind is wind only, soft and cool. I wait by the airplane. I wait for a friend to come and teach me to fly.

The distant seashell hush of a small-town morning is in the air, whispering along with the early wind. You have missed much, city dweller, the words trace in smoky thought. Sleep in your concrete shell until the sun is high and forfeit the dawn. Forfeit cool wind and quiet seashell roar, forfeit carpet of tall wet grass and soft silence of the early wind. Forfeit cold airplane waiting and the footstep-sound of a man who can teach you to fly.

“Morning.”

“Hi.”

“Get that tiedown over there, will you?” He doesn’t have to speak loudly to be heard. The morning wind is no opponent for the voice of a man.

The tiedown rope is damp and prickly, and when I pull it through the lift strut’s metal ring, the sound of it whirs and echoes in the morning. Symbolic, this. Loosing and airplane from the ground.

“We’ll take it easy this morning. You can relax and get the feel of the airplane; straight and level, a few turns, look over the area a bit…”

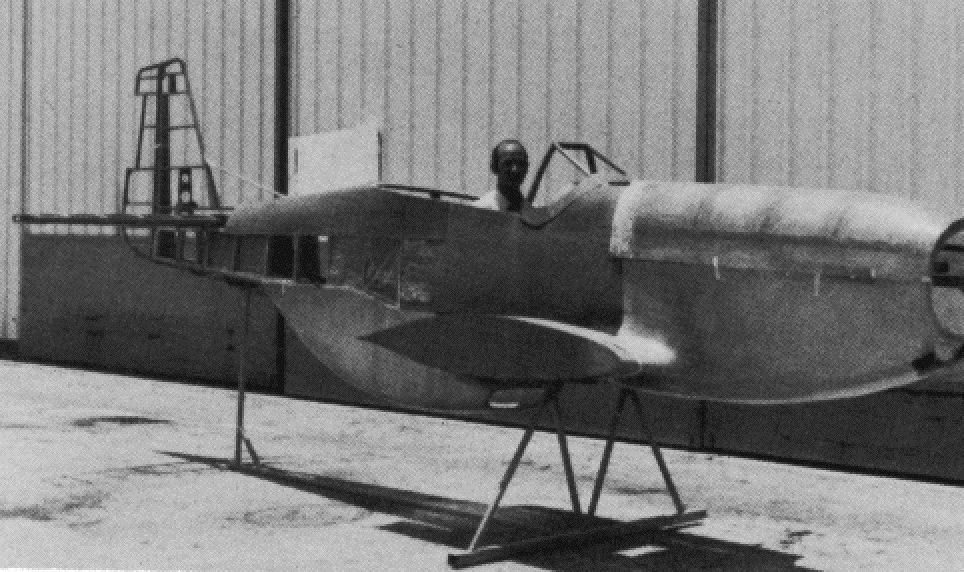

We are settled in the cockpit, and I learn how to fasten the safety belt over my lap. A bewildering array of dials on the dashboard; the quiet world is shut away outside a metal-doored cabin fitted to a metal-winged, rubber-tired entity with words cast into the design of the rudder pedals. Luscombe, the words say. They are well-worn words and impartial, but flair and excitement were cast into the mold. Luscombe. A kind of airplane. Taste that strange exciting word. Luscombe.

The man beside me has been making little motions among the switches on the bewildering panel. He does not seem to be confused.

“Clear.”

I have no idea what that means. Clear. Why should he say clear?

A knob is pulled, one knob chosen at this moment from many same looking knobs. And there goes my quiet dawn.

The harsh rasp of metal against metal and gear against gear, the labored grind of a small electric motor turning a great mass of engine metal and propeller steel. Not the sound of an automobile engine starter. A starter for the engine of an airplane. Then, as if a hidden switch was pressed, the engine is running, shattering stillness with multibursts of gasoline and fire. How can he think in all this noise? How can he know what to do next? The propeller has been a blur for seconds, a disc that shimmers in the early sun. A mystic, flashing disc, rippling early light and bidding us follow. It leads us, rubber wheels rolling, along a wide grass road, in front of other airplanes parked and tied, dead and quiet. The road leads us to the end of a wide level fairway.

He holds the brakes and pushes a lever that makes the noise unbearable. Is there something wrong with the airplane? Is this flying? We are strapped into our seats, compressed into this little cabin, assailed by a hundred decibels running. Perhaps I would rather not fly. Luscombe is a strange word and it means small airplane. Small and loud and built of metal. Is this the dream of flight?

The sound dies away for a moment. He leans toward me, and I toward him, to hear his words.

“Looks good. You ready?”

I nod. I am ready. We might as well get it over with. He had said it would be fun, and had said the words with the strange soft tone he used, belying his smile, when he truly meant his words. For that meaning I had come, had left a comfortable bed at five in the morning to tramp through wet grass and cold wind. Let’s get it over with and trouble me no more with your flying.

The lever is again forward, the noise again unbearable, but this time the brakes are loosed, and the little airplane, the Luscombe, surges ahead. It carries us along, down the fairway.

Into the sky.

It really happened. We were rolling, following the magic spinning brightflashing blade, and suddenly we were rolling no more.

A million planes I had seen flying. A million planes, and was unimpressed. Now it was I, and that green dwindling beneath the wheels, that was the ground. Separating me from the green grass and quiet ground? Air. Thin, unseen, blowable, breathable air. Air is nothing. And between us and the ground: a thousand feet of nothing.

The noise? A little hum.

There! The sun! Housetops aglint, and chimney smoke rising!

The metal! Wonderful metal.

Look! The horizon! I can see beyond the horizon! I can see to the end of the world!

We fly! By God, we fly!

My friend watches me and he is smiling.

0 Comments